Get CB in your inbox

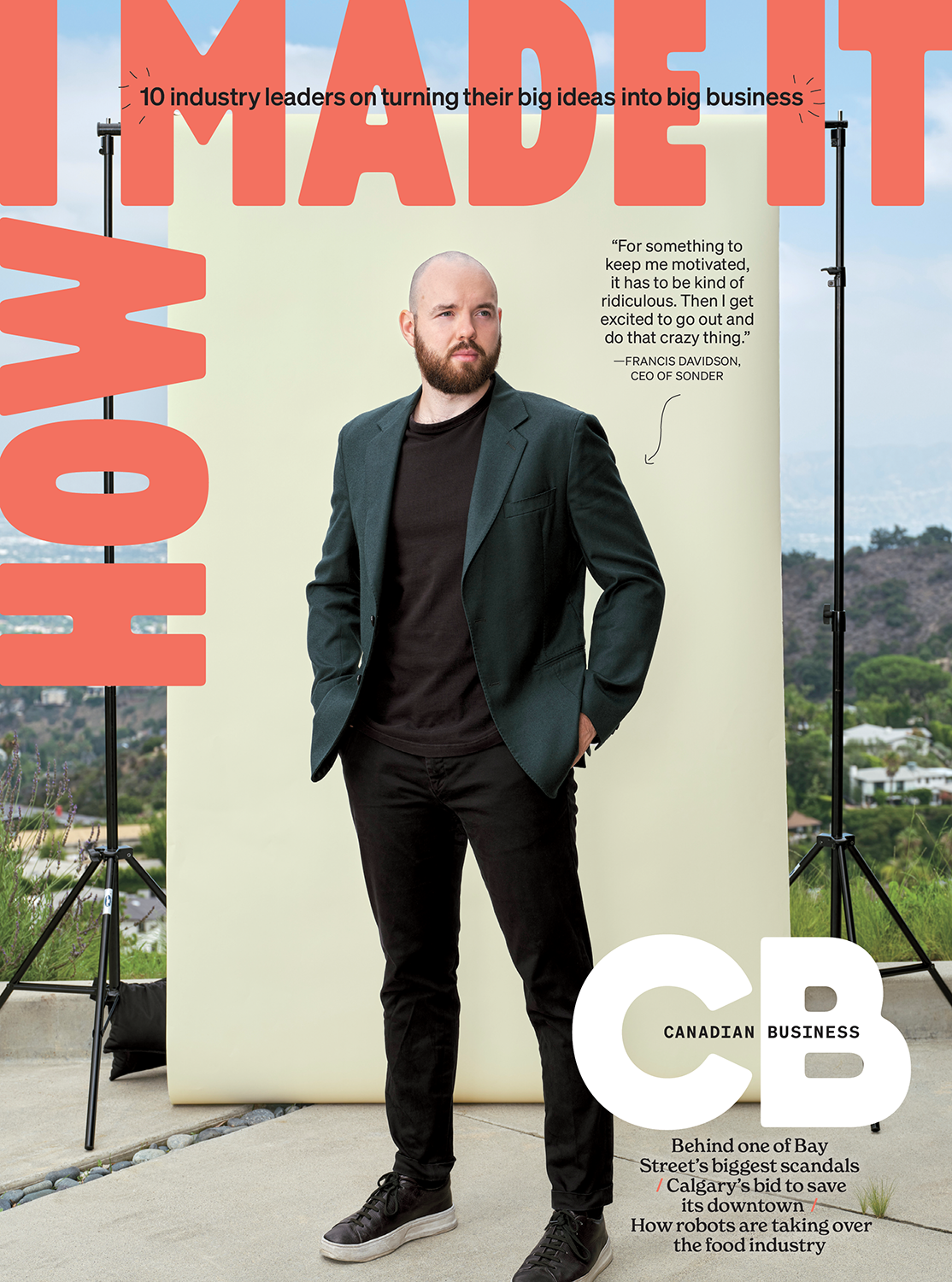

Get the print edition

Published four times a year, delivered straight to your door. Access best-in-class journalism about the innovation economy and the inspiring individuals leading the charge in the newly redesigned CB magazine.